In January 2023, Professors Willy Shih and Mike Toffel led more than 40 HBS MBA students on site visits to witness the energy transition and innovative sustainable production activities throughout Denmark and the Netherlands, in their new Immersive Field Course (IFC). This is one of 13 student essays posted on the HBS Business and Environment Initiative’s Blog that highlights their reflections. Learn more about this IFC course on Decarbonization and Sustainable Production by watching this five minute video summary.

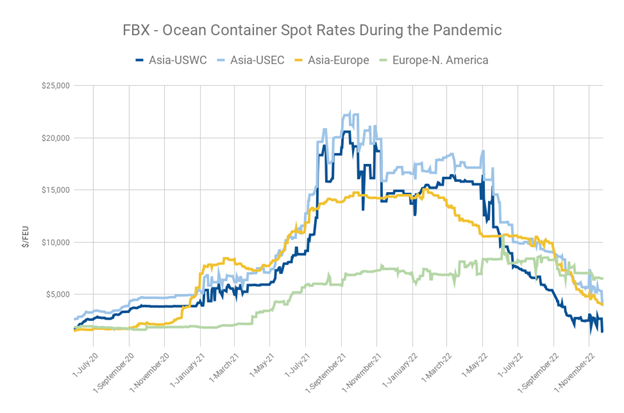

As part of our immersive field course (IFC) on decarbonization and sustainable production, our group visited Maersk, one of the world’s largest shipping companies with 707 vessels and Denmark’s largest company ($81.5B in revenue in 2022), 206th on the Fortune global 500 rankings. Maersk was at the epicenter of recent supply chain turbulence, with shipping rates increasing more than fivefold over 2021 and 2022.

Maersk’s decarbonization strategy

While many consumers and businesses struggled with rising transportation costs, Maersk’s ability to charge higher rates generated historic ocean shipping revenue of $48 billion and earnings before interest and taxes (EBIT) of $18 billion, for a margin of 37%. This was in contrast to the traditional low-margin nature of the shipping industry, as Maersk’s typical EBIT target is 6%. As we listened to speakers at Maersk’s HQ, it was clear that they felt this was a transitory windfall as shipping rates have already largely fallen to near pre-COVID levels. However, due to Maersk’s unique structure as run by the AP Moller family foundation, there was an opportunity to re-invest this profit into long-term investments that aligned with the company’s decarbonization goals.

Maersk has a unique scale that makes its decarbonization targets particularly important, with the company singlehandedly responsible for approximately 0.1% of global carbon emissions. It was surprising to see how bought-in Maersk was to decarbonization, including their commitment to cut emissions per shipping container by half and cut terminal emissions by 70% by 2030, and their recently accelerating their net-zero targets from 2050 to 2040. Maersk views decarbonization as an opportunity to achieve a long-term competitive advantage while doing the right thing, rather than an imposition or a burden.

According to Maersk leadership, the two keys to their decarbonization strategy are:

- Strong relationships with customers to get them on board with paying a premium to help fund these decarbonization efforts, and

- Collaboration with suppliers to dramatically increase supply of green shipping fuels.

Maersk’s massive scale means that they can essentially create a new market for sustainable shipping fuels, which they are doing in biomethanol. While there is a chicken-or-egg problem for sustainable shipping fuels—investing in new fuels is risky because anticipated demand might not materialize, and investing in ships that rely on new fuels is risky because ample fuel supplies might not materialize—Maersk is solving this by making a long-term commitment to green methanol (which includes biomethanol and e-methanol) by buying 19 massive ships that will be powered on green methanol over the next three years. This sends a signal to suppliers to develop more of the fuel by guaranteeing that they will purchase it. One of our speakers described the roughly 20 different fuels that were considered before they landed on green methanol, a very different choice from ammonia that some competitors are planning to use. Given the massive investment Maersk is making in green methanol, it was fascinating to see how the people behind that decision dealt with the uncertainty over what will end up being the best sustainable fuel for the long term.

When looking at decarbonization strategies, it’s important to remember that greenhouse gas emissions are just one part of the puzzle – and safety, availability, reliability are all important factors that must be considered as well. For example, even if nuclear power becomes technologically feasible for ocean shipping, Maersk believes that legal, safety, and public perception challenges make it highly impractical as a primary energy source. Similarly, with biomethane, Maersk sees emissions slippage risks as outweighing fuel efficiency benefits.

Maersk’s culture reflects their aggressive decarbonization goals

Another interesting facet of our visit was a discussion with Maersk’s government affairs director. He talked about how new rules by the International Maritime Organization (IMO)—a UN agency that sets rules for international shipping—will require significantly lower emissions and higher efficiency for maritime shipping, and how Maersk actively supported these requirements. Maersk felt like many of these regulations were long overdue, and that these rules could provide a framework to put pressure on all shipping companies to become more sustainable, rather than just those in countries like Denmark where it is already a priority. In fact, Maersk’s government affairs director expressed disappointment in the fact that shipping was not included in the Paris Climate Agreement, which he believed could have set stronger international standards and speed the pace of decarbonization in the shipping industry. Furthermore, Maersk is actively campaigning in support of a $150/ton of carbon tax, which could increase costs in the short-run but would actually make maritime shipping more competitive relative to other forms of freight like air and truck that have higher rates of carbon emissions.

Finally, a fascinating thing about Maersk was seeing the culture of the company itself. While we were expecting a shipping company to have a staid, corporate environment, the campus HQ felt lively and innovative, with a large cafeteria full of vegan and other options that felt like something out of a Silicon Valley tech giant. Further, sustainability felt baked into all decision-making, rather than just a check-the-boxes exercise, with an understanding that the future of the company hinges on a successful decarbonization strategy.

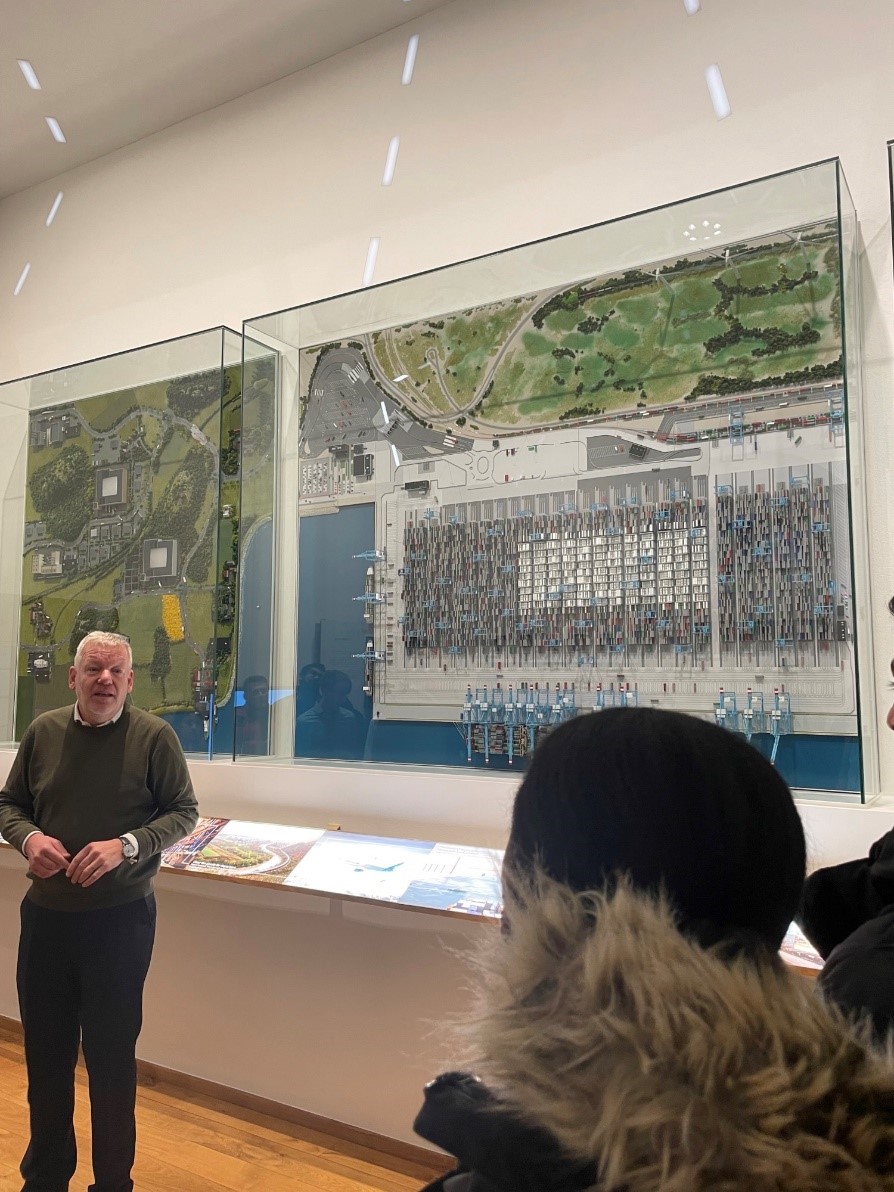

We closed out our trip with a visit to the Maersk museum, which highlights the company’s history and values. Maersk’s company historian (yes, that’s a real job!) gave us a guided tour and showed how maritime shipping evolved to become the massive, highly optimized industry that we see today.

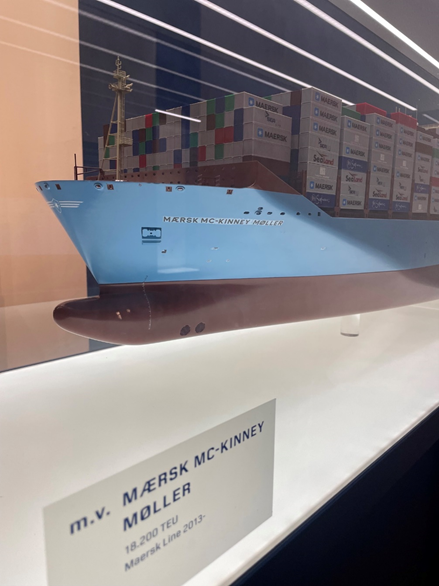

In the museum, we were fascinated by how ships have kept growing in size, with a model of the Maersk Mc-Kinney Moller, which was the biggest ship in the world when it was built, able to handle 18,000 TEUs (twenty-foot equivalent unit containers).

In a serendipitous twist of fate, that same ship was at the Port of Rotterdam when we visited a few days later. While it was cool to see the model of the ship, the in-person scale is something that must be experienced in person and provides a great reminder of just how massive the infrastructure is that goes into basically everything we buy in today’s globalized economy.

-----

Read more posts in the IFC Series:

Deconstructing LEGO’s Decarbonization

Port Esbjerg: Deploying Offshore Wind

HySynergy and Crossbridge Energy

Grundfos: Innovation & Inspiration for Sustainable Product Design

Arla Foods: How Sustainable Can A Dairy Company Be?

Amager Bakke: A Look into the Future of Waste Incineration

Maersk’s Journey to Decarbonize Shipping

BTG Bioliquids: Creating Fast Pyrolysis Bio-Oil from Biomass Residue Streams

Grolsch Brewing Company: Drink Sustainably

Van den Ende Rozen: Greenhouse Rose Production